Austin Collings provides this profile feature after listening to audio recording 001 and meeting up with Robert. Photography by Chinese Francis.

Rob is off the booze and everything else so we meet in Al-Faisal Tandoori in the Northern Quarter. You get a decent curry for a decent price in there (not easy in the Northern Quarter where even a plate of sauce-less chips is priced like property). The curry is served with cutlery that has a certain weightless, flat and dated feel like it should be held only in a primary school canteen. Harmless knives from another age.

It sits next to the infamous Millstone pub. One of the last old-boozers still standing and still supping. Inside, the afternoon karaoke is cranking up. Outside, two half-cut Geordies are having a cig’ and both half-shouting down – and also at – their mobile phones as if it’s the late 90s and mobile phones are new and unusual. All of this – the cutlery, the cheap(er) curry, The Millstone, the dinosaur drinkers, the recent-old just hanging on in this ruthless age of genocidal gentrification – makes sense to Rob’s story of survival and romanticism.

“I grew up in Openshaw, East Manchester, where City’s ground now is. Around the decay of Victorianism: the mills, broken people, broken hearts, broken toes, broken minds.”

Almost stereotypical, his voice is pure Mancunian: a rough wrinkle that sails through the afternoon air, catering to truth rather than drama.

Now 55, he is a collage maker of sound and we’re here to talk about his new album – Audio Recording 001. The James Bond-like ‘00’ is misleading as he has released 50 solo albums and seven albums with his first group Gabrielle’s Wish prior to 001.

Discipline for him is: how much can I get away with? He is as prolific as his old mate Mark E Smith, but now he’s ditched the lead-singer mantle, he deals in a limitless sprawl of sound over words. Impulsive, erratic, brilliant, relentless sometimes very simple and very naked, a cell without dimensions, it is less something to listen to and more something to colour the air around you. Sonic colour.

“In the 70s as a very small child there was always music in the house through my Nanna who I’d go round to all the time, listening to the ‘wireless’. Not the radio: ‘How dare you say ‘the radio,’’ she used to say. We’d listen to Radio 3, old English stuff like Vaughan Williams. We’d also watch black & white films. I found them magical: the lighting, the soundtrack.

But what really gave me a kickstart was my school – Clayton Brook Primary – they did a day out to Seymour Road School in Clayton. And what they had on was Peter & The Wolf. Big cinema screen with an orchestra beneath it playing a live score. I couldn’t take my eyes off the orchestra. It captivated me and it’s had me in a gilded cage ever since.”

As a teenager, in the late 70s, he was a fully converted music-junkie and it was a good time to get your fix: Sex Pistols, The Buzzcocks, The Clash – the usual names. He earned his dough with a paper round and trousered ‘extra bangers’ delivering ‘The Pink Paper’ or ‘Saturday Final’ as some blokes called it. Pre-Teletext and pre-internet, ink still smudgeable on banner headlines, here was where you got your football scores after the Saturday matches had finished. Rob was the kid who’d pick up the stack of papers and scurry around the boozers in Openshaw, dropping it off to half-cut and full-cut blokes dreaming of a big win on the pools or just dreaming of their team winning for once. (A slight aside, the final whistle was called on The Pink Paper this year. No more ink on your fingers. Another one gone in Rob’s world.)

Clutching his ‘spends’, he’d haunt Gorton Market for vinyl. He could feel his eyes opening.

“I’d always go by myself. I’ve always liked to be on my own. I liked being in the shop around all this stuff, trying to understand what it meant. There was a divine spark going on within me but I couldn’t work it out, what music was doing for me. There was some kind of connection like when William Blake talks about with the grain of sand, seeing a world in a grain of sand. That’s what I was trying to understand in music. Just being around records shops and seeing all this stuff.

You could put your paws on it. All the records were behind the counter but all the sleeves were displayed at the front of the shop, in plastic sleeves. You’d bump into these other music heads, give ‘em the nod and all that. All of us treasure hunting.

I was so precious of my records that I hid them. But I hid them on top of the dryer. I came home one day from school and they’d all warped. Devastated.

Then I started getting in to the Manchester stuff that was coming out: Joy Division, The Fall etc. Plus, all the rock and disco. My ears were completely open to everything. Even classical music. I wasn’t closed off. My Nanna would play me Jim Reeves and the production was phenomenal. Then I’d be listening to film scores and Leonard Cohen.

There was no not listening to anything and there was no slagging it off. I worked that out myself.”

Exploring the limits of personal freedom, he was always on the lookout for spiritual escape. This is what happens to many kids – societal whipping boys and girls – who have no home life to comfort them and are bamboozled by school. They seek escape and enchantment.

“The breakdown of the family in the 70s and 80s. The Frankfurt School of subversion and all that kind of bollocks. I could see that breakdown in my own family which traumatised me. It still does. Still to this day, I can shed a tear. I was so young I can’t quite remember the details. Music was the escape. It gave me solace, another language. I was always trying to be the higher self, the better person. As a child I didn’t understand that. I felt like there was a master-slave relationship with the community around me. People polluting me. Taking energy from me, having this relationship with society: you must get the job, you must do this: all that being drilled in to you.

You had to run the gauntlet of the generations above you. Will I get beat up and all that on the streets. I used to think: is this how it is, because this is scary. Another freedom for me alongside music was my pushbike. That got me away. My Raleigh Racer. I thought I was the dog’s bollocks and at that age I probably was. I’d get lost on purpose and try and find my way back home. To make myself scared. Never quite sure where I was.

I liked being with nature. The elements. Reading the sky. Listening to the wind. My Nanna always spoke to me about stillness. But I never could get it. Because I was a young man. I didn’t realise what it was.”

Herein I’m reminded of the Billy Caspar character in Barry Hines book KES and Ken Loach’s film adaptation: that bold, melancholy and magical masterpiece about a runt of a kid with no purpose until he befriends a kestrel. After which, he creates his own earthbound Arcadia. Swap the kestrel for records and you have young Rob (and countless other kids out there).

This yearning for escape informs his new album. He sounds like he’s creating the music to create the space he’s not finding in life?

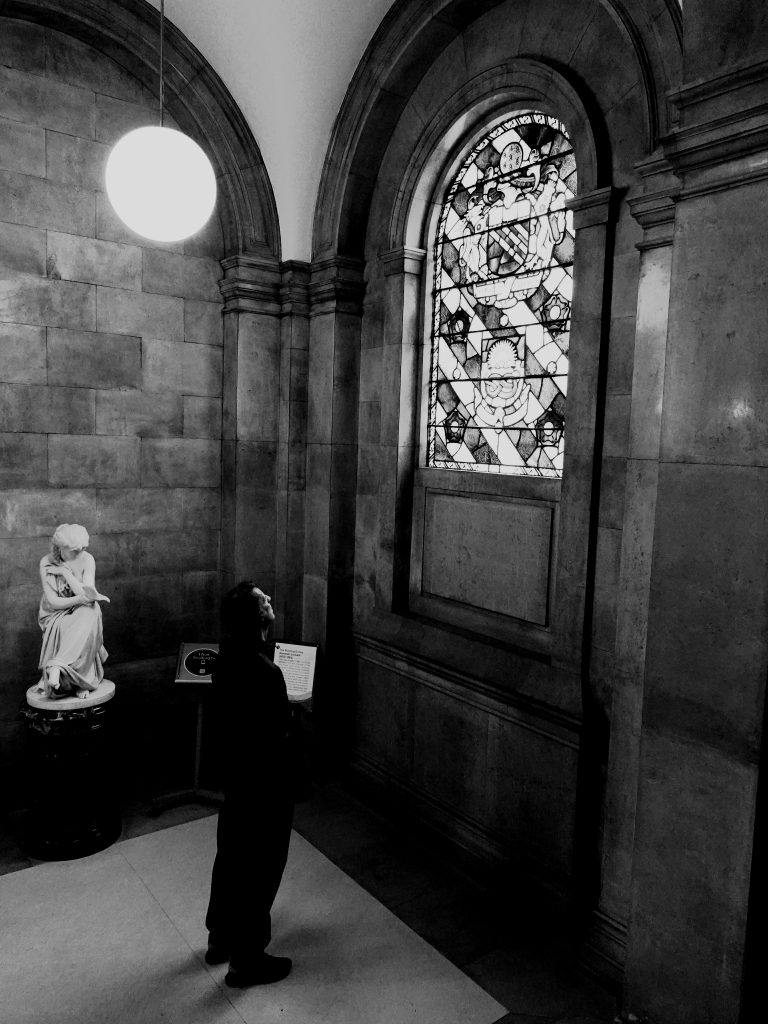

“Very true. It’s about the ruination of Piccadilly Gardens in Manchester. While I’m sat there [in Piccadilly Gardens] on a plinth, on the altar, at the feet of Queen Victoria, I’m surrounded by the solidity, the concrete, the violence and the shitness and the misery, people’s scowling eyes. Everybody is just passing by. Everyone is on the black mirror: the phone. Less science-fiction, more science-fact.

People might think I’m crackers, but the energy from the old mental institute that used to be there may be playing a part in it. Mother earth will give off energy. There’s something wrong: that’s the word. Wrong.

It reminds me of that C.G. Jung quote: “People will do anything, no matter how absurd, to avoid facing their own souls.” I’m not slagging it off. What needs repairing is the human consciousness. It’s so disconnected from anything. But it’s given me a subject. The city has done something interesting to me here.”

Days later, he sends me a link to a Manchester Evening News story. Headline: Manchester is the second unhealthiest area in England, according to a new study.

Some may say the measure of love is loss, and losing his best mate and band guitarist (in Gabrielle’s Wish) Tim Walsh Jr. to suicide in 2019 is yet another hole in a place he knew so well: both inside himself and in the boozers and studio in Manchester. The suicide: he never saw coming. Nobody did. The terrible duty: to live oneself.

“Tim Jr. was a big part of my life as a friend and listener. Really intelligent man. We spent a lot of time on the piss together. Not much of a talker. Very introverted. But not unsociable. The opposite in fact: he’d socialise with people whilst I’d be sat in the shadows, sulking. He always said: ‘You’re a right miserable cunt, but I love you’. What he wasn’t saying was interesting. Even now, when I’m done recording, I’ll turn around in my chair and go to speak to him, to get his view on what I’ve just done, thinking he’s still there.”

It wouldn’t be right to leave it on this sad note, so I ask him about his time spent with some of my favourites: Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard and Chuck Berry.

“I worked with Uncle Chuckles as I called Chuck Berry for about 3 years. That nickname didn’t go down too well as he wasn’t a laugh-a-minute. I did sound engineering. Music production. Travelled all over Europe.

I used to work for the promoter Alan Wise. I loved him dearly, Alan. As Alex DeLarge says in Clockwork Orange: I could be a right bastard with no manners. Well, Alan could be, but he was also a beautiful man.

Alan brought all these acts over to Manchester around 2003-2004 and I worked with Little Richard, Jerry Lee-Lewis and Donovan. The majority of them were the biggest shower of cunts I’ve ever worked but Donovan was a gentleman.

Little Richard: absolute bellend. He called me in to see what I was about, this Manc. doing the sound etc. He’s brought his own engineer over with about 16 hanger-onners. My attitude was: I don’t give two fucks. If he wants his engineer working it then work it, I’m still getting paid. I ended up doing it anyway. He called me in to his dressing room before a show and all you could smell was sausage as in man-sausage. Penis. There was man smell everywhere. Bad man smell. And there were five mannequins with all different syrups (syrup of figs – wig – rhyming slang) for the time of the day and I burst out laughing. I thought: that is amazing. And he’s looking at me laughing, totally baffled.”